Wonderful 100: Rehabilitation Soldiers at NC State

This edition of Special Collections News looks at the rehabilitation program that North Carolina State College conducted after World War I ended (1918) to provide vocational training for disabled veterans.

Veterans and Vocational Education

The U.S. government established a rehabilitation system for World War I veterans that focused on returning disabled veterans to work, unlike the pension system created for Civil War veterans. Under this new system, disabled veterans would return to work and become self-supporting again; many believed this crucial in making the men feel "whole” again. (Not coincidentally, some thought rehabilitation would be cheaper for the government in the long run than pensions.) Vocational training taught new job skills to veterans whose disabilities prevented them from returning to their pre-war employment. The government contracted with various institutions around the country, including NC State, to provide this training.

NC State already had experience with vocational education. In the 1890s, the college began holding short courses (and later summer schools) for people other than regular college students seeking 4-year degrees. In 1917, the U.S. government began providing funding to land-grant colleges for vocational education, and NC State created a department to oversee teacher-training courses and agricultural education. During World War I, the college also trained 320 soldiers “in carpentry, blacksmithing, electric wiring, dynamo tending, and automechanics [sic],” according to the 1919 Agromeck yearbook. The U.S. government then tapped NC State after the war to provide vocational training for disabled veterans.

The Rehabilitation Men

NC State’s administration originally planned to integrate the disabled veterans (called “rehabilitation men,” “rehabilitation soldiers,” and “rehabs”) into 4-year degree programs, but this immediately proved impossible. In his 25 May 1920 annual report to the Board of Trustees, President W. C. Riddick stated, “a large majority of these men, by reason of their poor preparation, were unable to enter our regular classes.” In his biennial report for 1919-1920, Riddick also indicated that “the poor physical condition and poor preparation of many of these men make it rather difficult to give them proper instruction,” and in his other reports from the early 1920s he labeled them as “sub-collegiate grade.” The 3 Aug. 1922 Raleigh News and Observer stated, “some of these men were illiterates and many had reached only the fifth and sixth grades.” Despite the fact that these former servicemen were unprepared for college, Riddick said that the “Board of Trustees thought they were entitled to some share in the benefits of the College.” Therefore, NC State developed a separate rehabilitation program focusing on vocational training, and by the time it ended in 1925, hundreds of veterans had been trained.

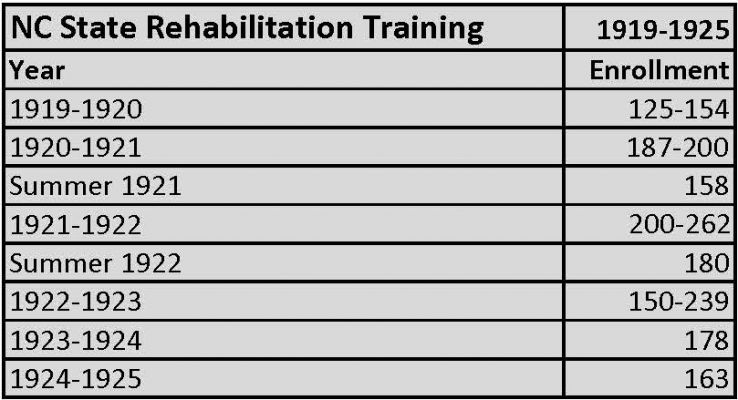

The exact number of NC State’s rehabilitation veterans is difficult to determine because the two main sources, the college president’s annual reports and the annual college catalog, often conflict. Nevertheless, it appears to have averaged between 150 and 200 each year from 1919 to 1925. Many of these men must have returned year after year because a 1924 Agromeck entry stated that the rehabilitation program had trained only 200+ men at that point after 4 years of operation.

In his annual reports, President Riddick frequently used the term “partially disabled ex-service men.” None of the documentation researched for this post indicated specific disabilities experienced by the veterans. NC State did not provide their medical care, which may have been completed elsewhere prior to their enrollment.

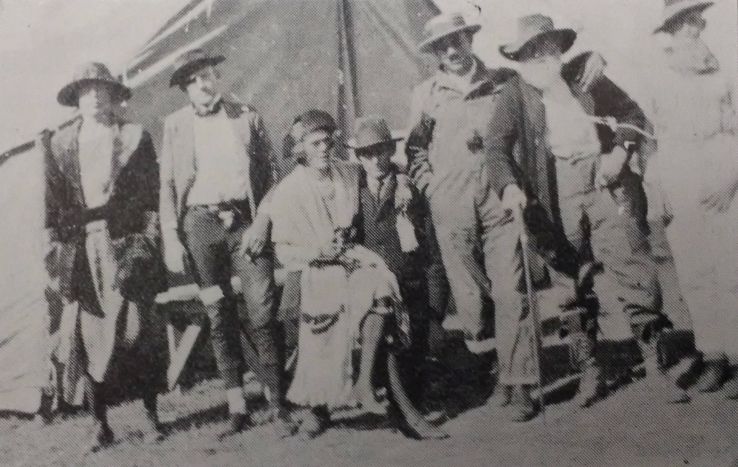

The rehabilitation men probably lived in the Raleigh area, but not on campus as the college struggled to house even the regular 4-year students at that time. Nonetheless, the college administration and the local community appears to have been welcoming. The Raleigh Red Cross chapter looked after the veterans’ “comfort and pleasure,” according to the 23 Dec. 1919 Raleigh News and Observer, and it held a reception for them on 6 Nov. 1919. The veterans said “this occasion will always remain in our memories as one of the pleasantest of our lives,” according to the Dec. 1919 Alumni News. Advertisers in the Technician student newspaper reached out to the veterans: for example on 16 Feb. 1920 a local café “extend[ed] to the boys of A & E, both students and rehabs., the hand of welcome.” The disabled veterans were included in a 4 July 1922 college picnic, at which they played a volleyball game against teachers taking a short course (the 5 July 1922 News and Observer reported that the teachers won).

In 1923 and 1924 the annual Agricultural Students’ Fair included rehabilitation student parade floats and performances of the Hayseed Fiddlers, a musical and comedy group comprised of disabled student veterans. Several of the rehabilitation men won prizes in the agricultural competitions, including the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd prizes in the 1923 poultry judging contest. Among the fair's midway shows, the judges awarded the Hayseed Fiddlers first prize in 1923, for performing "Turkey in the Straw" and other old fiddle tunes. According to the Dec. 1923 N. C. State Agriculturist, the college's quarterly publication of agriculture students, they "kept the crowd laughing at their jokes, songs, and square dances," and some spectators "paid the admission fee three of four times in order that they might see the same performance over and over." At the 1924 fair, the Alumni News claimed the Hayseed Fiddlers were one of “the most successful features” and the 7 Nov. 1924 Technician student newspaper called them “a drawing card” (it added that the performance was peppered with humor and brought back “bygone memories”).

The rehabilitation men, however, did not necessarily see themselves as smoothly integrated into the campus. An 8 Dec. 1922 Technician article claimed “they came here unwanted by the students, and they have been knocked, snobbed, and shunned until it seemed as if the limit of human endurance must soon be reached.” Yet with their “indomitable Tar Heel spirit,” they eventually attained “a place secure in the hearts of the students.”

In the Dec. 1923 N.C. State Agriculturist, one rehabilitation student who wrote about participating in the 1923 Agricultural Students' Fair stated that up until that point there had been an "indifference between the college men and those of the Rehabilitation Department," but he quickly added "we feel this indifference is being put aside, and in its stead a spirit of co-operation is springing up." As an example of this new "co-operation," he stated that the rehabilitation students had been included in the 1923 fair, whereas they had not been "encouraged to take an active part" in previous fairs.

A few rehabilitation men founded a club called “The Triangle” in order “to establish a fraternal feeling among themselves,” The group apparently restricted membership, however, and did not open itself to all disabled veterans on campus. In fact, this organization may have been very exclusive and included only a small number of rehabilitation men enrolled in 4-year degree college programs.

Agricultural Training

The “first duty” of NC State’s rehabilitation program was “to educate these men to make a living despite their physical handicaps,” as stated in the 1924 Agromeck. Most disabled veterans here studied agriculture. Each specialized in a “branch in which his particular disability will least interfere with his success.” According to the May 1920 college catalog, “emphasis is put on field study and use of illustrative material" for agricultural training, and students were engaged in practice for a considerable amount of their time. The catalog stated

For the men who will continue their studies it is a preparatory course. For those who will return to the farm it gives some understanding of the principle underlying their work, and brings them into contact with agencies which serve the farmer—the State College, the [North Carolina] Department of Agriculture, and the State Experiment Station. For men who have had no farm experience the course will be supplemented by additional field practice. Opportunity will be given these men to grow some of the common field crops and to care for some farm animals.

The May 1920 catalog also showed that general training occurred during the first term and specialized training in cotton, tobacco, peanuts, poultry, swine or beef cattle in the second. The catalog of the following year revealed the program had become more complex, with coursework delineated in 4 grades, each with 3 16-week terms. That suggested a 4-year, 12-month training program. General instruction in reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, and biology occurred early on, and specialized training in farm crops, animal husbandry, horticulture, and poultry took place in the last 2 grades. Perhaps few veterans availed themselves of such extensive training because by 1923 the curriculum had simplified to 1 year of introductory agriculture and 1 year of specialization. Beekeeping, fruit growing, and farm mechanics were added by 1923, agronomy and dairying by 1924. If the veteran had less than a 5th-grade education, however, a year of “supervised study” preceded this training. Classroom instruction took place in Patterson and Ricks Halls; field practice occurred on the college farm and in some cases on privately owned farms nearby.

Industrial Training

During the first few years of NC State’s rehabilitation program, the college provided industrial training in addition to agricultural. At least ¼ of the rehabilitation students received training in engineering, textiles, auto mechanics, drafting, electrical work, machinery, carpentry, and similar trades. In 1922, the college had to discontinue industrial training, because, as President Riddick indicated in his annual report submitted in May of that year, it was “seriously interfering with the work of our regular [4-year college] students.” In his 1921-1922 biennial report, he said rehabilitation “monopolized our equipment and made it impossible to give the necessary instruction in shop work, drawing, etc. to the students in our regular classes.” The April 1922 Alumni News said as many as 100 students were leaving because the college could not guarantee the 30-hours per week of shop time that the government required. Textiles students may have remained, however, as suggested by the 23 Mar. 1923 Technician.

4-Year Students

Some veterans had enough prior education that NC State admitted them into 4-year degree programs. The college did not always keep separate statistics on those men, so their number cannot be determined. According to articles in the 3 and 13 Aug. 1922 Raleigh News and Observer, there were approximately 60 veterans enrolled in regular agricultural, engineering, and textiles classes at that time. The newspaper stated, “some have won scholarship honors, others wear monograms won by hard work on Riddick Field [i.e., they played on the football team], still others lead in literary work and serve as class representatives in the student government.”

Growing Outreach Programs

Because of the “poor preparation” of many rehabilitation men, the college hired additional teachers to provide remedial instruction, but President Riddick frequently stated in his annual reports that U.S. government funding fully covered the additional expenses. In 1922, the U.S. Veterans Bureau sent Frank Capps to NC State to coordinate the training program, and he organized a Rehabilitation Department that had 12 instructors by April 1923, according to the college catalog. By 1924 the university had appointed Capps to serve also as director of College Extension and listed him as a faculty member. College Extension oversaw NC State’s short courses, summer schools, correspondence courses, and vocational education programs, as well as the short-lived rehabilitation training program. It was the seed that eventually grew to become the McKimmon Center for Extension and Continuing Education.

In 1925 the U.S. government discontinued funding for the veteran rehabilitation program. NC State College President E. C. Brooks stated (in his 1924-1925 Board of Trustees report) that

this was a fine attempt on the part of the Government to repair the injuries done a certain class of our young men by the war, and restore them to society as fully prepared at least to support themselves as they were when they entered the war. The Government, cooperating with such institutions as State College, did accomplish this purpose in a very large number of instances. Some were equipped to enter new trades, others who developed an ambition to receive a college education were transferred into regular college work. Some of these have already graduated with credit to themselves and to the College. However, a large per cent of them came to the institution with little academic training, and so far as possible the instruction was adapted to their needs. The college has been helpful in aiding such men not only to overcome their impediments, but in preparing them to reenter their communities as self-governing and self-directing individuals.

As far as the college was concerned, the rehabilitation training program succeeded in making the disabled veterans independent, self-supporting, and “whole” again. The 1924 Agromeck concluded that these men were “carrying on successful projects in their home communities, and making a satisfactory living for themselves and their families.”

Sources for this Special Collections News post include the Agromeck, Technician, Alumni News, and college catalog issues linked above. (The catalogs from the early 1920s also list the names of many rehabilitation students. See 1920 for an example.) The college presidents' annual reports also provided information about the rehabilitation program. They are not available online, but they exist in paper copy in the Office of the Chancellor Annual Reports (UA 002.002, collection guide online). Likewise, the Dec. 1923 N.C. State Agriculturist contains further information about the rehabilitation students, especially their participation in the Agricultural Students' Fair. It is available only in paper form. To access these, please submit a request to the Special Collections Research Center. The Raleigh News and Observer issues from the 1920s are available to NC State students and faculty through Newspapers.com. For an overview of the U.S. military's rehabilitation program (focusing mostly on medical or physical rehabilitation), see Beth Linker's War's Waste : Rehabilitation in World War I America (NC State students and faculty can access online.)